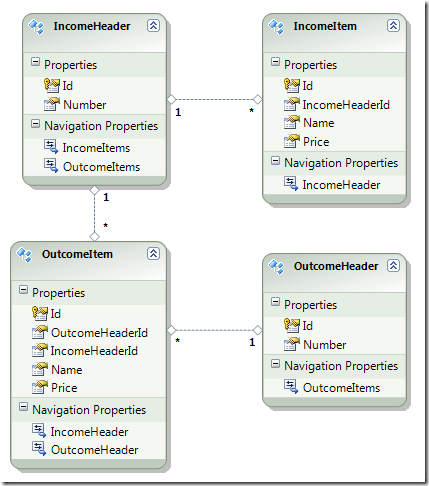

We all know what ‘IN’ clause is about – we want records where a field value matches one of the specified variants. Let’s imagine the following model although it may seem artificial at first but it actually reflects a situation you can find in a goods tracking software:

So we have income and outcome documents. Each document has a header and a number of items. An outcome item also has a link to a corresponding income document, or technically a header of an income document. That link is important because for one of our business reports we want to show what items have been sold and who were their suppliers. Well, there can be lots of other purposes but that’s not the focus of the post.

So I was debugging a problem in a typical LOB application one of these days and there was a similar model (a bit more complicated, of course) and at the data layer I hit upon the following method:

public OutcomeItem[] GetItemsByIncomeHeaderIds(

IEnumerable<int> incomeHeaderIds)

{

using (TestDbEntities context = new TestDbEntities())

{

var items = from item in context.OutcomeItems

join id in incomeHeaderIds on

item.IncomeHeaderId equals id

select item;

return items.ToArray();

}

}So this is a resource layer implementation of an operation that needs to return outcomes for a specified number of income documents. What strikes you at first is the the choice a developer made to accomplish the goal – a join of database items and the provided list of income document ID’s. It’s not going to result in a SQL query that uses ‘IN’ clause, instead it results in a query like this if we pass it 3 ID’s (1, 2, 3):

SELECT

[Extent1].[Id] AS [Id],

[Extent1].[OutcomeHeaderId] AS [OutcomeHeaderId],

[Extent1].[IncomeHeaderId] AS [IncomeHeaderId],

[Extent1].[Name] AS [Name],

[Extent1].[Price] AS [Price]

FROM [dbo].[OutcomeItems] AS [Extent1]

INNER JOIN (SELECT

[UnionAll1].[C1] AS [C1]

FROM (SELECT

1 AS [C1]

FROM ( SELECT 1 AS X ) AS [SingleRowTable1]

UNION ALL

SELECT

2 AS [C1]

FROM ( SELECT 1 AS X ) AS [SingleRowTable2])

AS [UnionAll1]

UNION ALL

SELECT

3 AS [C1]

FROM ( SELECT 1 AS X ) AS [SingleRowTable3]) AS [UnionAll2]

ON [Extent1].[IncomeHeaderId] = [UnionAll2].[C1]See how ugly it is? It’s transforming our provided list of ID’s into SQL constructs but, wait, that’s not all. Check out what’s happening when you pass it 4 ID’s (1, 2, 3, 4):

SELECT

[Extent1].[Id] AS [Id],

[Extent1].[OutcomeHeaderId] AS [OutcomeHeaderId],

[Extent1].[IncomeHeaderId] AS [IncomeHeaderId],

[Extent1].[Name] AS [Name],

[Extent1].[Price] AS [Price]

FROM [dbo].[OutcomeItems] AS [Extent1]

INNER JOIN (SELECT

[UnionAll2].[C1] AS [C1]

FROM (SELECT

[UnionAll1].[C1] AS [C1]

FROM (SELECT

1 AS [C1]

FROM ( SELECT 1 AS X ) AS [SingleRowTable1]

UNION ALL

SELECT

2 AS [C1]

FROM ( SELECT 1 AS X ) AS [SingleRowTable2])

AS [UnionAll1]

UNION ALL

SELECT

3 AS [C1]

FROM ( SELECT 1 AS X ) AS [SingleRowTable3])

AS [UnionAll2]

UNION ALL

SELECT

4 AS [C1]

FROM ( SELECT 1 AS X ) AS [SingleRowTable4]) AS [UnionAll3]

ON [Extent1].[IncomeHeaderId] = [UnionAll3].[C1]Do YOU see where it’s getting at? See the tendency? If you pass it a lot of ID’s (say 2000 or more) it’s going to fail like this:

"Some part of your SQL statement is nested too deeply. Rewrite the query or break it up into smaller queries."

Although that join works pretty damn fast and it’s probably acceptable when you know the number of request parameters is limited at a reasonable level, it’s not at all acceptable when you need this piece of code to be scalable up to no limits.

The ‘IN’ clause might solve our problem here but we also know that it can be REALLY heavy when the number of arguments you put in it is big. How much big? Not too big really, you’re going to start straining the database with 1000 already.

The second problem with ‘IN’ clause is that different databases have different limits on the number of arguments you can put into it. It’s primarily dictated by resource/performance reasons. SQL Server 2008 allows you to put a lot more than other well-knows databases out there but it still has limits and one day it’s going to strike you with this:

"Internal error: An expression services limit has been reached. Please look for potentially complex expressions in your query, and try to simplify them."

Still, let’s see how we should form our LINQ query to trigger the ‘IN’ clause to be generated:

public OutcomeItem[] GetItemsByIncomeHeaderIds(

IEnumerable<int> incomeHeaderIds)

{

using (TestDbEntities context = new TestDbEntities())

{

context.CommandTimeout = 600;

var items = from item in context.OutcomeItems

where incomeHeaderIds.Contains(

item.IncomeHeaderId)

select item;

return items.ToArray();

}

}The ‘Contains’ method on the collection does the trick. Now given the problem described above let’s rewrite our method so it becomes robust and scalable against any number of provided arguments:

public OutcomeItem[] GetItemsByIncomeHeaderIds(

IEnumerable<int> incomeHeaderIds)

{

using (TestDbEntities context = new TestDbEntities())

{

IList<IEnumerable<int>> parts =

new List<IEnumerable<int>>();

List<int> allIds = new List<int>(incomeHeaderIds);

while (allIds.Count() > 0)

{

int take = allIds.Count() > 1000 ? 1000 :

allIds.Count();

IEnumerable<int> part = allIds.Take(take);

parts.Add(part.ToList());

allIds.RemoveRange(0, take);

}

List<OutcomeItem> list = new List<OutcomeItem>();

foreach (var part in parts)

{

list.AddRange((from item in context.OutcomeItems

where part.Contains(item.IncomeHeaderId)

select item).ToList());

}

return list.ToArray();

}

}We don’t allow more than 100 arguments to be included in the query. It’s probably not the ideal number and it’s worth more testing to identify one but to prove my point let’s run the method against 20000 ID’s. When we put them all in 1 ‘IN’ clause the query executes in 2.22 minutes but when we run the last version that actually yields 20 SQL queries it finishes in 8 seconds!

‘IN’ clause is expensive. Don’t let too many arguments to be put into it.

One crazy idea: what if we take this approach of splitting parameters in parts but instead of using the ‘IN’ construct we will use the original join solution? Well, the truth is we won’t be able to feed 1000 arguments at a time. It’s limit is about 40 and in addition to ugly SQL it gives us about 19 seconds in total. More than 2 times worse compared to ‘IN’. But on the other hand, 40 at a time means it had to execute 500 queries! That proves that these queries are a lot faster than those using 'IN'. Still, when it comes to scalability this solution loses.

Bottom line: it’s ok to use ‘IN’, it works reasonably fast with a reasonable number of arguments, don’t let this number exceed 1000 (hm, who wants to run a few tests and come up with the ideal number?) and you’re going to be fine in terms of performance and scalability.