Events are an important concept of domain-driven design as they are the primary mechanism that enables entities within an aggregate to communicate with the outside world, be it other aggregates or other bounded contexts.

There is a common problem that developers face when implementing domain events. How do we make them reliable? That is, how can we make sure they are consistent with the state of the aggregates that triggered them?

The ultimate solution might be event sourcing when we make events themselves to be the primary source of truth for the aggregate state. But it may not always be feasible to implement event sourcing in our existing domains or it can be quite a paradigm shift for many developers. Often, it will be considered an overkill for the task at hand.

If our data and our events are separated when should we fire them? And how can we handle them reliably?

If we fire them before completing the business operation and the completion fails we will need to take compensating actions to undo changes caused by the events (which may not even be possible when the events have triggered operations in external systems beyond our control). If we fire them after completing the business operation there is a risk of failure happening just before sending the events resulting in inconsistency between the triggering aggregate and the components that should have been notified of the change.

I'm going to walk you through an approach that I've been applying in my projects and that seems to have been serving well so far. It's not a universal solution as it presents certain requirements towards your storage (mainly the ability to atomically persist multiple pieces of data).

You can check out my sample playground app BookFast that makes use of the ideas described in this post. I'm going to be giving links to certain files and provide code samples in the post but to get the whole picture you might want to examine the solution in an IDE.

Event groups

The approach that I'm using splits all domain events into 2 groups which have different triggering logic:

- Those that are atomic with the originating aggregate. These are in process plain domain events that get fired and handled within the same transaction as the changes in the originating aggregate. These events should not trigger activities in external services.

- Those that are eventually fired and handled. They get persisted atomically together with the originating aggregate and dispatched by a separate background mechanism. Integration events naturally fall into this category but it is possible to route events targeting the same bounded context through the same mechanism if eventual consistency is acceptable or asynchronous activity is required.

There is a good argument that you may not need the first group of events and can just sequentially invoke operations on involved aggregates in your command handler which can make the code/workflow more obvious to follow. At the same time I prefer the have highly cohesive handlers that should not be modified as I need to add behavior to the workflow.

You should also consider the way you design your aggregates. An aggregate form a consistency boundary for a group of entities and value objects within it. You should evaluate if the operation spanning multiple aggregates kind of suggests that you may just need to have a single aggregate. But be careful here, smaller aggregates are generally preferred.

But what if my operation requires another action in process and at the same time an integration event to be published? Create two separate event types and raise both. It's a small issue (if an issue at all) but it preserves versatility of the solution.

Prerequisites

For the proposed approach to work you need to make sure to implement what Jimmy Bogard described as a better domain events pattern. In other words your domain entities should not raise events immediately. Instead they should add them to the collection of events that will be processed at around the time that the business operation is committed.

Here's an example of a base Entity class that enables this pattern:

public abstract class Entity<TIdentity> : IEntity

{

private List<Event> events;

public void AddEvent(Event @event)

{

if (events == null)

{

events = new List<Event>();

}

events.Add(@event);

}

public virtual IEnumerable<Event> CollectEvents() => events;

}There is a collection of events to be published and the virtual CollectEvents method enables aggregate roots to collect events from child entities.

Another prerequisite is the raisable Event class. I'm using Jimmy Bogard's MediatR library to handle commands and events dispatching so all events should implement INotification marker interface.

public abstract class Event : INotification

{

public DateTimeOffset OccurredAt { get; set; } = DateTimeOffset.UtcNow;

}To support eventual events (group 2) we need another base class called IntegrationEvent:

public class IntegrationEvent : Event

{

public Guid EventId { get; set; } = Guid.NewGuid();

}These events must be uniquely identifiable so it is possible to determine if an event had already been processed on the receiving side.

A better name for group 2 events would probably be AsynchronousEvent as they can be used to trigger asynchronous actions within the same bounded context as well.

Reliable events flow

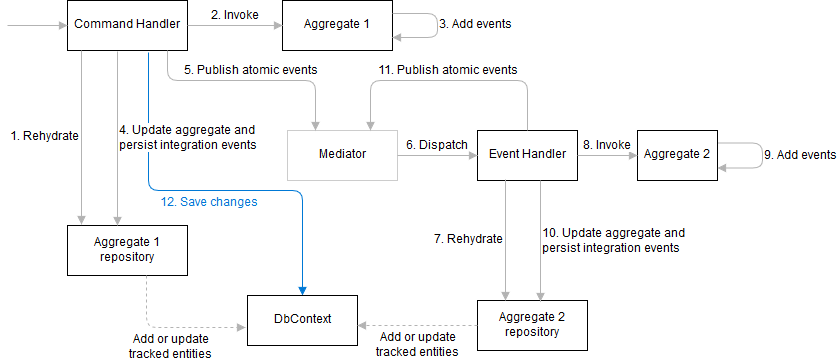

Let's have a look at the flow of processing a command (e.g. a web request) that involves working with several aggregates and handling their events.

Normally command and event handlers perform 4 distinct tasks when processing requests or events:

- Rehydrate an appropriate aggregate from the storage

- Invoke operations on the aggregate

- Persist the updated aggregate

- Process events

The last two tasks are what makes this whole story complicated when entities' state and events are separated. In the approach that I'm using these tasks are transformed into the following:

- Persist the aggregate's changes together with integration (eventual) events (step 4 on the diagram). This step should not commit these changes to the underlying storage. When using EF Core it merely means adding changes and events to the

DbContextand saving them to the database yet. - Raise atomic events and wait for the completion of their processing (step 5 on the diagram). This can trigger a chain of similar cycles when downstream event handlers raise events of their appropriate aggregates. We're not completing the operation until all events get processed.

- Commit changes to the storage (step 12 on the diagram). When using EF Core this is when we call

SaveChangeson the context.

It works with EF Core really well as by default your database contexts are registered as scoped instances when calling IServiceCollection.AddDbContext meaning that within a given scope (e.g. processing a web request, or a dequeued message) various repositories (which are responsible for various aggregates within the same bounded context) will get injected the same instance of the DbContext. Calling SaveChanges on the context will atomically persist all changes to the database.

Alternately, you could wrap the whole operation in an ambient or explicit transaction and not rely on the Entity Framework's behavior of wrapping the final save operation in a transaction. But be mindful about locks being held for longer periods as event handlers do their work.

Here's an example of the SaveChangesAsync extension method that I'm using that handles all of these tasks:

public static async Task SaveChangesAsync<TEntity>(this IRepositoryWithReliableEvents<TEntity> repository, TEntity entity, CommandContext context)

where TEntity : IAggregateRoot, IEntity

{

var isOwner = context.AcquireOwnership();

var events = entity.CollectEvents() ?? new List<Event>();

var integrationEvents = events.OfType<IntegrationEvent>().ToList();

if (integrationEvents.Any())

{

await repository.PersistEventsAsync(integrationEvents.AsReliableEvents(context.SecurityContext));

context.NotifyWhenDone();

}

foreach (var @event in events.Except(integrationEvents).OrderBy(evt => evt.OccurredAt))

{

await context.Mediator.Publish(@event);

}

if (isOwner)

{

await repository.SaveChangesAsync();

if (context.ShouldNotify)

{

await context.Mediator.Publish(new EventsAvailableNotification());

}

}

}It requires that repositories implement IRepositoryWithReliableEvents interface that allows it to persist eventual events to the same database context as the aggregates themselves.

public interface IRepositoryWithReliableEvents<TEntity> : IRepository<TEntity> where TEntity : IAggregateRoot, IEntity

{

Task PersistEventsAsync(IEnumerable<ReliableEvent> events);

Task SaveChangesAsync();

}Calling SaveChangesAsync on the actual database context is done by the initial command handler and not the event handlers. This is achieved through the 'ownership' flag on the CommandContext instance. Only the first handler in the chain (which is the command handler) acquires the 'ownership' of the operation and thus is allowed to complete it. The CommandContext is a scoped instance (same as DbContext) and is shared between all handlers.

Here's an example of a command handler to make the picture complete:

public class UpdateFacilityCommandHandler : AsyncRequestHandler<UpdateFacilityCommand>

{

private readonly IFacilityRepository repository;

private readonly CommandContext context;

public UpdateFacilityCommandHandler(IFacilityRepository repository, CommandContext context)

{

this.repository = repository;

this.context = context;

}

protected override async Task Handle(UpdateFacilityCommand request, CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

var facility = await repository.FindAsync(request.FacilityId);

if (facility == null)

{

throw new FacilityNotFoundException(request.FacilityId);

}

facility.Update(

request.Name,

request.Description,

request.StreetAddress,

request.Latitude,

request.Longitude,

request.Images);

await repository.UpdateAsync(facility);

await repository.SaveChangesAsync(facility, context);

}

}It's worth repeating that UpdateAsync method on the repository should not call SaveChangesAsync on the DbContext. The same is true for repository methods that add new entities to the context. It has an implication that you cannot use the Identity column to get the database to generate identifiers for new entities. You can still use database managed sequences though (EF Core supports hi-lo pattern and provides AddAsync method on DbContext for that) or choose to generate identifiers yourself.

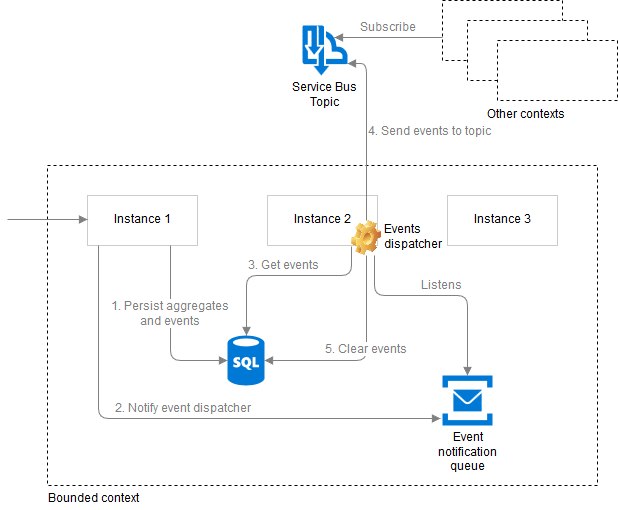

The EventsAvailableNotification is used to send a message to the eventual events dispatcher that monitors the persisted events in the database and forwards them further (normally to a queue or a topic).

Eventual (asynchronous) events

Let's now consider the second part of the reliable events flow which is dispatching of persisted asynchronous events.

Steps 1 and 2 on the diagram are what we've already seen the SaveChangesAsync extension method. This is when the job of the original command handler is done and the rest of the processing happens asynchronously relative to the original operation.

Reliable events dispatcher is a singleton background process per bounded context. We need a single instance to manage the persisted events table in the database. We can implement a singleton across service instances using a distributed mutex (the pattern is also known as Leader Election). There are various approaches to implement the mutex, my sample solution uses the blob lease technique (in fact, it's a .NET Core version of the Patterns and Practices team's implementation).

The dispatcher's job is to basically poll the database table periodically and dispatch the events further by sending them to the Service Bus topic. We don't want it to poll the database too often thus it performs checks every 2 minutes. At the same time we want the events to be dispatched sooner after they get raised so the dispatcher also supports a notification through a dedicated queue. We need a separate notification queue per bounded context as the dispatcher may end up running in a different instance of the service as the one processing the request (like on the diagram the dispatcher is running in instance 2 and the request was processed by instance 1).

The events get cleared from the database only when they get successfully sent to the topic.

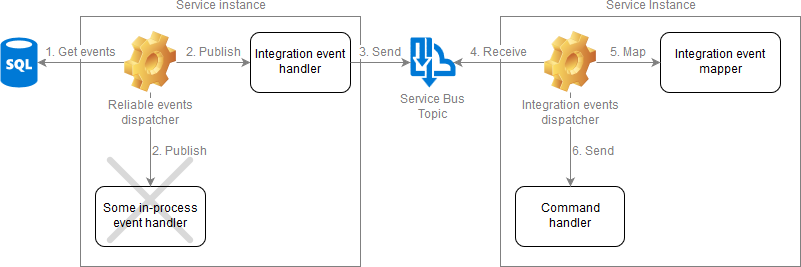

Handling events

With atomic events it's straightforward: you just add a INotificationHandler implementation for the event you want to handle and the mediator will invoke it when you publish the event.

Things get more complicated with asynchronous events. If it's an integration event it's apparent that we want to send it to a messaging system (such as Azure Service Bus topic) so it gets dispatched to subscribers.

However, asynchronous events can also be used within the same bounded context that triggered them. For instance, you want to call an external service but you don't want to make the current operation wait for the result. Or you have a denormalizer that flattens several aggregate's data into an efficient query model.

So you create asynchronous events for these kinds of operations (both integration as well as just asynchronous) but you should not create event handlers for them!

The thing is that the reliable events dispatcher is a singleton process (per bounded context) and it should not wait for the completion of our asynchronous operations. Its job is to drain the pending events queue from the database as quick as possible by sending those events to a robust messaging system (such as Azure Service Bus). That's why there is basically only one handler for integration/asynchronous events that just sends them to the messaging system.

On the receiving side there is an integration events dispatcher/receiver that maps events to commands (using a service specific mapper implementation), constructs a new scope, establishes a proper security context and actually invokes a command handler. It also makes sure to handle application specific and unknown errors that might be thrown.

Unlike the reliable events dispatcher on the sender side, the integration events receiver runs in every instance of the service and listens to the service specific subscription of the topic, effectively implementing the Competing Consumers pattern that balances the workload on the service and improves scalability.

Handling asynchronous events as commands insures that they follow the same flow as the original operation.